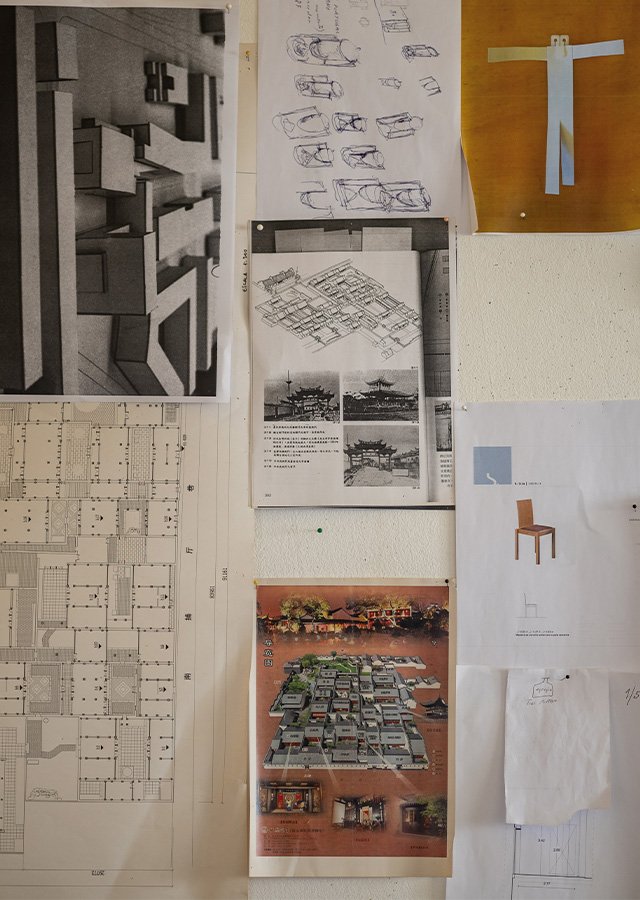

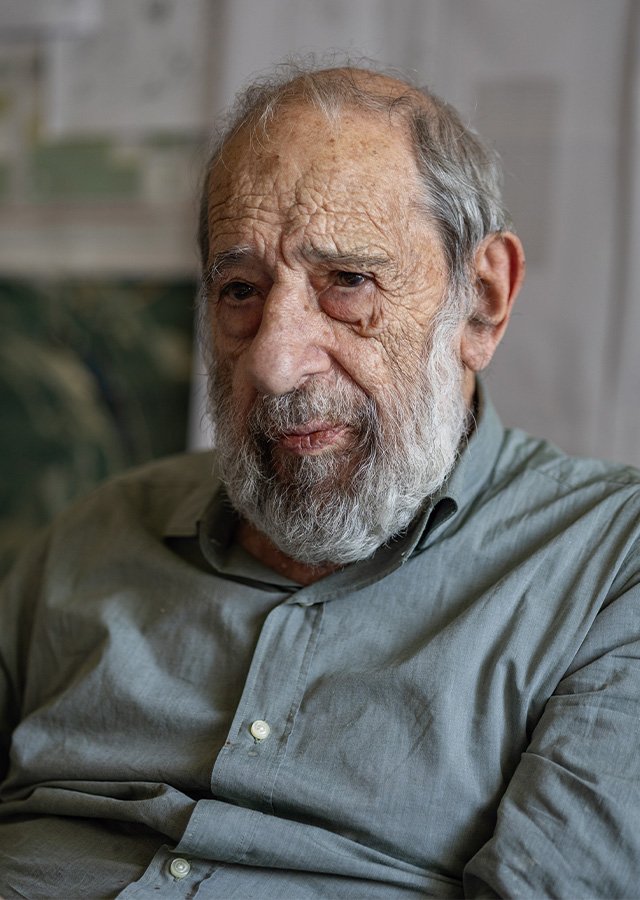

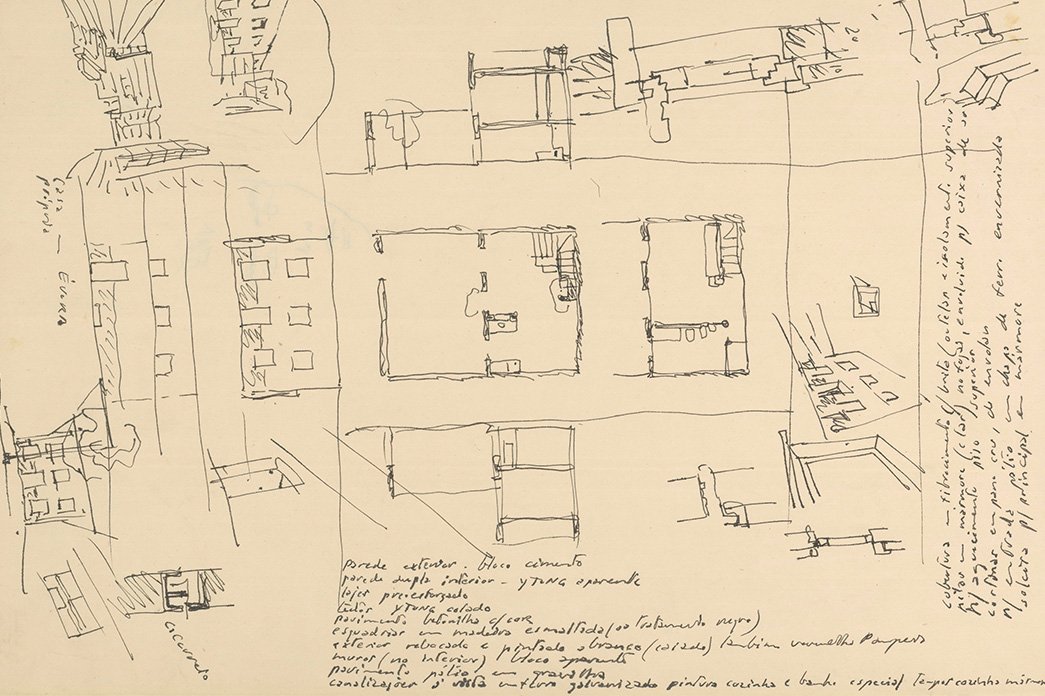

He has turned drawing lines into the guiding principle of his life, which has propelled him into a career of national and international recognition. From the Pritzker Prize to the Leão de Ouro, from social housing to museums and art centres, Álvaro Siza Vieira’s work continues to be a benchmark for new generations of architects. At the age of 91, hiseveryday life continues to be dominated by his craft, which he says is essential to prevent him from getting even older. In his studio he channels the inspiration he absorbs from the buzz of the city, continuing to design a unique legacy on a daily basis.

Tell us a bit about your daily life...

Is it here, in your studio, that you spend most of your time?

Yes, because I can’t travel, I have back problems. If

I didn’t, I would be travelling, because I do most of my work in China and

South Korea. But now it’s work-from-home.

Even though you’re not travelling nowadays, where do

you go for inspiration?

The inspiration is in the air, it’s in the cities...

Inspiration doesn’t come from within, it comes from the outside. It enters

through the eyes and goes up to the head, and therefore there is no shortage of

stimuli, references for ideas to come and innovation to take place. And there

is no shortage of history, which is so abundant in Portugal. And then there’s

the movement of the cities, multiplied, because everything is connected these

days.

Does coming here and continuing to work and do what

you love help in keeping you young? Does an artist never get old?

No, it has to be... If I didn’t work, like any mortal,

the only work would be mental and physical ageing, which is what you do after a

certain age. But working means thinking, taking responsibility, which is

fundamental, if only to avoid ageing even more.

Having lived

through so many different eras, including in terms of architecture, how do you

think about it today as it faces such concrete challenges? For example, the

issue of sustainability and even a new spatial concept of the home... How is

architecture thought of today?

The concept of

sustainability has always existed. A house has been a shelter, a place for the

family to rest and develop for centuries. Now there are new demands, basically

for a better way of life, but on the other hand, there are also greater

drawbacks. The increase in the idea of sustainability in all debates is also

closely linked to unsustainability. There are also more demanding problems,

because there is more foreseeable oversight, let’s call it that.

Do you think there is a generalised idea that

architects only work for the rich?

This is one of the unbelievable distortions that are

part of the campaign against architects, which in principle also means against

architecture. Architects have always assumed they work for the masses. In the

1920s and 1930s, the most notable works of architecture, by the most celebrated

architects, were for social housing. This is the legacy of those years. The

idea that architects only work for the rich is an invention, a regrettable

distortion, which only stems from other interests, but let’s not go there.

You have worked all over the world... Is there a city

or country that particularly fascinates you in terms of architecture?

To a certain extent, every country has something

particularly interesting about it. I like all cities and all countries, some

for one reason and some for another. Then, of course, there are the pinnacles

of beauty, but this isn’t general, although the personality of the people is

always present. If we think about Paris, Venice, Naples, New York, there’s a

particular intensity, a particular authenticity... This may include a lot of

fake stuff, but what remains is the authenticity. When skyscrapers grow like

plants in New York, this is not the architects’ whim, but economic and social

concessions. Now, when you put up a tower at the foot of the [Arrábida] bridge

that is taller than the bridge or than a national monument, the result is a bad

one. That’s not to say that it’s ugly, but rather that it’s inappropriate, it’s

fake, it lacks authenticity.

We have more and more foreigners with a lot of money

who are investing here. Do you think Portugal has luxury potential?

There are luxuries, but there are also inequalities,

and they are very evident. Portugal is very peaceful. But everything that

exists in other countries also exists here. There will also be some interest

due to a certain underdevelopment in relation to other countries. But I think

that many people come because they find it more peaceful, they are beginning

not to come because of the cost of living. This is the main reason I see. The

climate, the natural and built beauty, the presence of history in the landscape

and perhaps a little, too, the major differences in the landscapes of such a

small country.

You also work a lot with the Asian market. What are

the challenges in working for these countries?

I almost only work for the Eastern market; in Portugal

I have very little work. The experience I have is in China and South Korea.

Excellent working conditions. And the number one reason is clients who want

quality, who treat architects very well, who don’t say that they are capricious

and who provide good working conditions. You can feel a desire to do things

with quality. Such a thing is rare here.

Do you see yourself as a man from Oporto? Do you value

your roots?

I like living in Oporto, apart from having friends,

etc., I even like it from the point of view of the climate. Oporto is also a

city with a beautiful physical backdrop. It’s the river... Oporto exists

because the river exists. It has great geographical and climatic conditions

and, as such, this is also one of the reasons why historically it has very good

architecture. I feel good here... Now I regret not being able to travel. It

would be great to get out and see other things... You can’t have everything.

Do you feel adequately recognised in Portugal or is

there a lack of recognition?

Sometimes it even makes me uncomfortable... I have a

lot of interviews, for example (he laughs)... For some people there is

recognition, for others there isn’t... As always. What there is now, and this

is the overall feeling, is actually a very harsh relationship with architects

as professionals. I’m not complaining personally, nor do I see anything

personal in it. If you talk to other architects, you’ll see that it’s not whinging,

but that the conditions really are terrible and that most of the impositions

come from the European Community, so they’re repeated in every country except

Switzerland, which is the only country where you can work in architecture in

peace. Here, for example, copyright no longer exists. An architect no longer

has the copyright he used to have. That’s tremendous. There really is this

weakness in the demand for quality, it’s obvious and it’s starting to show in

the landscape.